Headlines of The Day

COVID homecare can’t cover the home stretch in India

India’s $5.4 billion homecare industry has everything you’ll need for home isolation, but everything also comes with a price. Sometimes hidden.

When a 53-year-old Gurugram resident tested positive for Covid-19 in early November, her foremost concern was the availability of a hospital bed in case her symptoms worsened. The Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR) has been facing a shortage of hospital beds for a while now. And with the Indian capital seeing a sharp spike in Covid-19 cases recently, the shortage has gotten all the more acute.

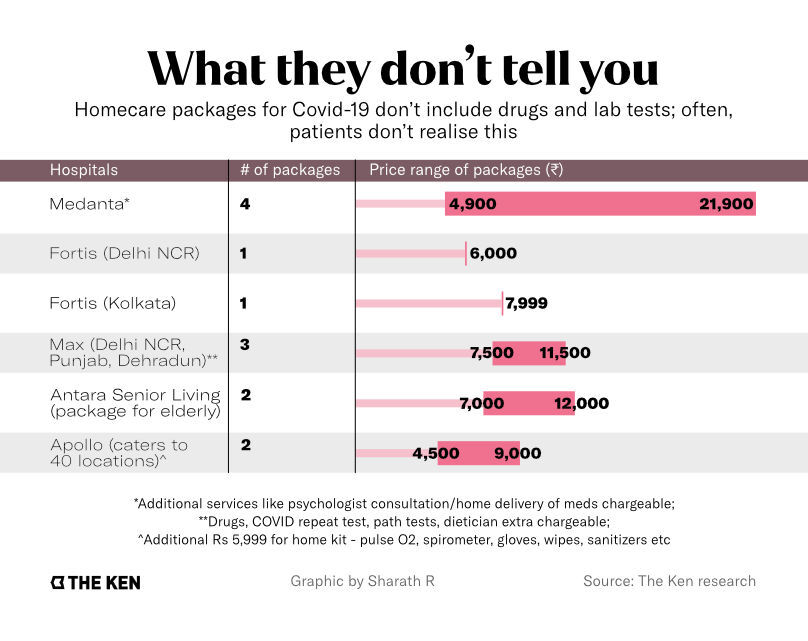

She explored her options; if she couldn’t be assured of a bed in a hospital, the next best thing was a homecare package. After some to and fro, she settled for one offered by Delhi-based private hospital chain Medanta. At Rs 4,900 ($70), it was the least expensive package available. The most expensive one was for Rs 21,900 ($300).

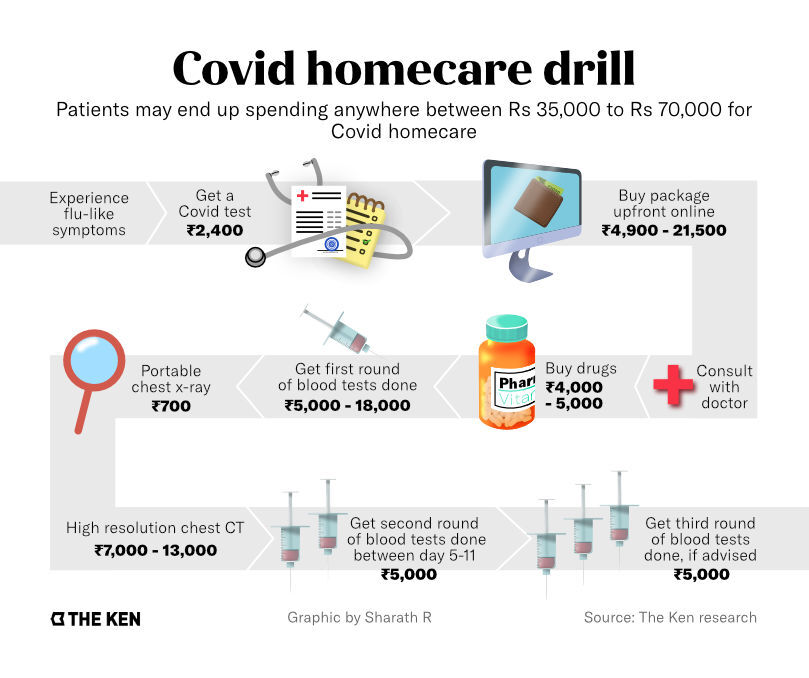

By the end of her 14-day quarantine period, her condition improved, but it came at a cost. She had ended up spending nearly 10X the amount she had paid upfront.

Her bills, which The Ken studied, revealed that she had spent close to Rs 20,000 ($300) on a string of lab tests. A D-dimer test, used to study blood clotting, set her back by Rs 1,900 ($25); kidney and liver function tests cost Rs 1,200 ($16) and Rs 1,350 ($18); and a Ferritin test was for Rs 1,250 ($17). All of these tests were priced at least 50% higher than market rates. She spent another Rs 8,000 ($108) on several drugs, including a week-long course of Favipiravir, an antiviral drug. CT-scans cost her Rs 7,000 ($100).

Halfway through the quarantine, when the doctor ordered another round of tests, she decided to compare prices with other pathology labs. “I realised that these were overpriced at Medanta. I could get them at a fraction of that cost from [lab chain] Dr Lal Pathlabs,” the patient told The Ken. “The government regulates prices of RT-PCR, but what about blood tests like IL-6 and D-dimer? Why is it letting some hospitals get away by charging such high prices?” Medanta did not respond to The Ken’s questions about their pricing decisions.

When the number of cases began surging earlier this year, hospitals were admitting all Covid-positive patients—even those with just mild symptoms. Eventually, though, the problem of available hospital beds reared its head. The government, initially unsure if home isolation was the best way out, only gave its nod for remote care monitoring in mid-May.

And while the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) quickly capped bed and treatment costs at hospitals, it left the homecare market unsupervised. Homecare entities sprung up overnight. For instance, a company named Life Express Healthcare, incorporated earlier this year, quoted between Rs 1.5 lakh ($2,000) and Rs 2.5 lakh ($3,400) for homecare services.

Instead of pushing for price parity, however, MoHFW batted for private hospital brands such as Max Healthcare, Fortis Healthcare, and Medanta—all traditional multi-specialty chains—in its best practices document accessed by The Ken. They began offering packages that included everything, from a simple “remote monitoring” deal that included teleconsults with doctors to more expensive and advanced packages that came with pulse oximeters, PPE kits, and home delivery of medicines and test results.

Standalone homecare startup Portea, which would later be debarred by Delhi’s Lieutenant-Governor Anil Baijal from providing services in the city, also found its way into MoHFW’s best practices for home isolation. Portea had initially quoted up to Rs 3,500 ($50) per patient to the Delhi state government in a non-tendered contract just for calling up patients for two weeks, said an official in the state government who did not want to be named.

Health secretary Rajesh Bhushan told The Ken that states’ procurement processes have improved and home monitoring costs have dropped. But patients are worried. Securing a hospital bed still remains a matter of influence and connections and if not, a frantic pillar-to-post run. Private homecare increasingly looks like an attractive option for patients with mild symptoms. Meanwhile, questions about check-ups and follow-up care in a fractured health infrastructure setup, especially in rural India, still remain unanswered.

The homecare regulation soup

Homecare under most state governments works like this: once a patient tests positive for Covid, the pathology labs report their contact details to the apex Covid coordination agency, the Indian Council of Medical Research. ICMR, in turn, alerts the patient’s respective state governments and district-level leadership. They forward this to private agencies hired by the government to place daily phone calls to the patient to check on their health.

But getting to this point wasn’t easy. The homecare response to the pandemic was marked by utter confusion and a lack of coordination. Delhi, for instance, had as many as seven Covid helpline numbers run by the state health department, the municipal corporation, and the National Health Mission. “There were times when citizens were dialling all of them back to back, but there was no response,” said Shuchin Bajaj, founder of private hospital chain Ujala Cygnus.

Meanwhile, midway through the pandemic, the Ministry of Home Affairs wondered if home isolation without any patient monitoring was contributing to the increase in Covid-19 cases in Delhi. While the government directed each case under home isolation to be physically verified by district teams, Baijal went a step further. He ordered every home-isolated patient in Delhi to undergo institutional quarantine for the first five days. The Lt Governor heads Delhi’s Disaster Management Authority.

The decision would turn out to wreak havoc on patient care. “I remember a middle-aged lady who had mild symptoms being ferried around in an ambulance all night long after five quarantine centres turned her away,” says Sonali Vaid, a Delhi-based health consultant, who volunteered her services with a Covid helpline for a few months. “She was diabetic and had not eaten a meal for six hours. It was horrific.”

The government realised quickly that it would be a logistical and a law and order nightmare, said an industry source who was present in the meetings led by the Ministry of Home Affairs. “They could not really drag people into institutions against their wishes, and better sense prevailed.”

Taking advantage of the desperation, private agencies quoted sky-high prices. In Karnataka, non-profit Piramal Swasthya pencilled out a monthly budget of close to Rs 3 crore ($405,200) for running Covid call centre services. State bureaucrats were shocked. And despite the prices, they still only got call centre agents who weren’t medically trained to handle the crisis. Piramal made no headway. The non-profit declined to respond to questions sent by The Ken.

In July, after Baijal ordered discontinuation of Portea’s services, Delhi floated a fresh tender offering Rs 2.5 crore ($337,000) over a period of three months to monitor an estimated 75,000 Covid patients under home healthcare. Prices were slashed down to a tenth, now at Rs 333 ($5) per patient. Noida-based HealthCare atHOME (HCAH), a home healthcare service provider backed by health and consumer goods company Dabur, won the bid.

HCAH is required to monitor 1,200 patients in Delhi daily, but the recent surge has seen up to 9,000 patients testing positive every day. At present, one in two Covid-positive patients in Delhi are not even receiving the first phone call from the state, officials manning Delhi’s triaging system confirmed to The Ken. “To the rest who cannot be called, we relay a text message including the state helpline number – 1800111747,” one of the officials said. Even as 40-50 emergency cases are referred to the state to be ferried to hospitals in ambulances, many slip through the cracks.

The terrifying uncertainty is what’s prompting patients to turn to private hospitals. The most common question patients ask when paying for homecare packages is: “Will I get a bed if my condition were to worsen? After all, I am paying so much.” All private hospitals offering a private homecare package that The Ken spoke to said the same thing—assuring a bed is impossible. “Doing so is unfair and unethical during a pandemic,” says Mahesh Joshi, chief executive officer of Apollo Homecare, the Chennai-based hospital chain’s homecare arm.

Around 200 out of the 10,000 patients that signed up for Apollo Homecare ended up needing a hospital bed; 10 of them needed ICU support. “There have been cases in the middle of the night when no bed was available and somebody needed an oxygen concentrator. We delivered it at home, or shifted the patient in our ambulance to Emergency where they were at least given a gurney till a bed was arranged,” says Joshi.

The hospital chain says it has serviced homecare across 40 locations since it began in late June. Fortis has taken a more conservative approach, restricting itself to offering homecare services only in Gurugram. It has catered to a little over a hundred patients in the city. It also runs homecare operations in Kolkata, but did not provide details.

Already in the game

Before the government and private hospital chains got deeply involved in the segment, established homecare companies had already picked up the baton.

Back in May, the Delhi government handed Bengaluru-based Portea a non-tendered contract to remotely monitor patients by making daily phone calls. The government paid half of the Rs 3,500 per patient Portea charged. Action Covid-19 Team (ACT), a fund set up by a group of venture capitalists and high net-worth individuals such as Azim Premji and Nandan Nilekani, paid the other half. Portea refused to engage with The Ken for this story or answer the questions posed to it on homecare and pricing.

While the Delhi government eventually discontinued Portea’s services, Karnataka opted to work with Swasth. Backed by the ACT, the in-app doctor consultation platform was built by an alliance of telemedicine and e-pharmacy startups, including the likes of Practo, Cure.fit, and 1mg. Sources in the Karnataka government told The Ken that Swasth was engaged for home-monitoring purposes. It is understood that between July and September, Swasth charged Rs 95 per call to monitor a patient for around five to six days. Its services cost the government Rs 24 lakh ($32,400).

Swasth’s CEO Ajay Nair, in his response to The Ken, categorically denied that the Karnataka government had paid the platform. He said that the government uploads all patient data on Swasth’s technology platform, which is then forwarded to three companies—Healthvista India, Portea’s parent company; HCAH; and the Hyderabad-based CallHealth Services. Except for Portea, the rates that the other companies charged the state for calling and checking on patients aren’t in the public domain.

While a simple phone call to check up on patients seems to be the rule of thumb for most homecare startups, volunteer-based pro-bono initiative Project StepOne goes a step further. Started by Bengaluru-based former entrepreneur TS Raghavendra, StepOne makes about 150,000 automated calls a day across India to patients. This is done in collaboration with 16 state governments.

The patients input their symptoms, with a request for a doctor to call back. An algorithm determines whether they receive a call-back or not. The group has around 7,000 volunteer doctors, of which 5-10% are active at any given point of time, and 2,000 paramedics on board.

Stopgap Arrangement

StepOne was engaged in home monitoring in Delhi for nearly two months, when Portea’s services were discontinued and HCAH was yet to be offered the contract. StepOne was asked to discontinue after HCAH came on board. It continues to offer it’s triaging services for free to Delhi.

StepOne tries to reach each patient three times. Those with worsening symptoms such as breathlessness, loose stools, very high temperature, and those over 65 are prioritised and called back manually, says Raghavendra. “First by non-medical professionals, then nurses, medical students, and later by doctors where there is a need to clinically examine a patient and mete out a prescription,” he says.

Different states engage StepOne for different aspects of homecare. While Delhi has tendered out home-monitoring to HCAH, it engages StepOne to triage the patient. In contrast to HCAH, StepOne also provides triaging services for free. It provided similar services in Karnataka too, before paid private agencies took over. In certain districts of Maharashtra—including Mumbai—and Bihar, it is also engaged in home-monitoring patients for the full haul of two weeks.

Till now, it has spent a total of Rs 75 lakh ($101,200) that it received in donation from ACT, the Omidyar Network*, and the Wadhwani Foundation.

Closing the loop

Whether it be state-sponsored homecare services or those offered by private hospitals, telemedicine is the common link. Even the most inexpensive packages offered by hospital chains have teleconsultations with doctors and remote monitoring by nurses baked into them.

The pandemic has been a catalyst for an industry that both doctors and patients once resisted. The telemedicine sector is now expected to reach $5.5 billion by the end of 2025, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 31%. The pandemic-induced push could mean that teleconsultation and e-pharmacy could comprise a whopping 95% of the telemedicine sector.

The pandemic has been a catalyst for an industry that both doctors and patients once resisted. The telemedicine sector is now expected to reach $5.5 billion by the end of 2025, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 31%. The pandemic-induced push could mean that teleconsultation and e-pharmacy could comprise a whopping 95% of the telemedicine sector.

However, the buck pretty much stops with the doctor and the patient on either side of the screen. Telemedicine, especially in rural areas of the country, is challenging because the health infrastructure is simply not in place. Patients often have to travel tens of kilometres to head to a healthcare centre or pick up medicines. The doctor can only advise the patient on what to look out for and when to head to the hospital. ‘Where’ and ‘how’ are big questions they may have no answers to. The loop is not closed.

While telemedicine—and by extension, homecare—is an “established care pathway across the globe”, Apollo Homecare’s Joshi feels that the Indian government has been late to embrace it. MoHFW finalised telemedicine guidelines only in March this year, followed by home-isolation guidelines for Covid-19 patients.

The $5.4 billion homecare industry is also expected to double by 2025, points out HCAH’s Srivastava. But if homecare services meted out by the government largely remain incomplete, and the patient loop isn’t closed, the guidelines serve little purpose on their own. Srivastava believes the government should go beyond and regulate the players in the industry. “Regulation will bring in quality standards among the players,” he says.

The Centre, though, wants to “wait and watch”. Union Health Secretary Rajesh Bhushan told The Ken that currently, the Centre is observing “best practices” employed by the states in Covid-19 home isolation routines.

Private players, on the other hand, feel that they will be able to provide superior homecare services as compared to their government counterparts. And that quality comes at a price point. “I agree that there has to be fairness, but who decides that fairness?” asks Apollo’s Joshi.

But does that warrant profiteering? Ujala Cygnus’ Bajaj thinks not. “In every business there is a very thin line between profiting and profiteering. In the medical profession, it switches very quickly. Some packages are overpriced, but it depends on people whether they should take it up or not.”

The 53-year-old Gurugram resident who sought Medanta’s services has since recovered, but the experience has taken the wind out of her sails. However, she’s now determined to do her research before jumping in, should a similar circumstance arise. A majority of India’s patients, desperately hoping to land a bed if their situation worsens, may not be able to do the same. The Ken